Competition from Nepalese teas — which has duty free access to the Indian market — has emerged as a lower-cost alternative to Darjeeling tea, challenging its viability.

IMAGE: A tea estate in Darjeeling. Photograph: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

Two years after opening its doors with the dream of bringing a fresh cuppa of Darjeeling tea — from the estate direct to the customers — Jay Shree Tea shuttered its flagship store in Lalbazar, central Kolkata.

Shops in the area claim to be selling “Darjeeling” tea, but at a much lower price. With a high cost of production, the Jay Shree store could not compete at that price point.

“They blend teas from Nepal and Darjeeling and sell it as Darjeeling. The Jay Shree Tea shop sold only its own garden teas, no blends of other origins. Hence we could not cope,” Vikash Kandoi, executive director of Jay Shree Tea & Industries, explained.

Competition from Nepalese teas — which has duty free access to the Indian market — has emerged as a lower-cost alternative to Darjeeling tea, challenging its viability.

More so if it’s passed off as Darjeeling, which is prohibited since the famed tea is a GI (geographical indication) product.

The tipping point

Darjeeling’s troubles go back to 2017 when the industry shut down for 104 days between June and September — crucial cropping months for the industry. Production fell to its lowest point at 3.2 million kg that year.

The near-absence of Darjeeling’s finest tea produce prompted some international packers to remove it from their assortment.

Nepalese teas — a poor cousin– made deeper inroads into the export and domestic markets. With significantly lower prices, it is undercutting Darjeeling teas by a wide margin.

A majority of the 87 gardens in Darjeeling manage to sell the first and second flush — the rich pickings covering bulk of the revenue for gardens.

“Competition from Nepal comes in after the second flush and most of the Indian demand is met by them. That’s a major issue,” Kandoi said.

The overwhelming factors impeding the Darjeeling sector are imports from Nepal and climate change, Arijit Raha, secretary general, Indian Tea Association (ITA), said.

Photograph: Reuters

Problems galore

Nepal is not the only problem. Low yield, high cost of production, labour absenteeism, climate change adversities — myriad challenges face the ‘champagne of teas’.

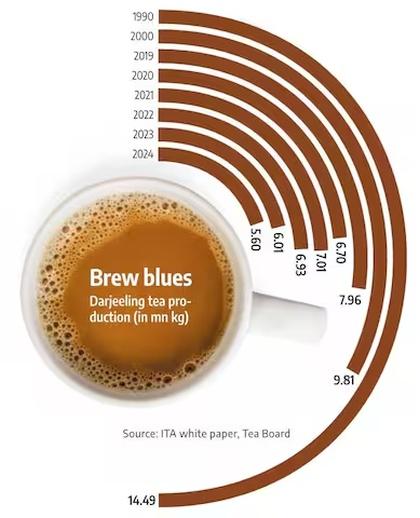

Last year, production of Darjeeling tea stood at 5.6 million kg due to adverse weather conditions — it’s the lowest except for 2017. But Darjeeling tea production has been in a steady state of decline for years now — in 1990, it was 14.49 million kg.

Dry spell has again hit the season’s first plucking. The first and second flush usually depend on the early rains received by the garden, B K Laskar, senior advisory officer, Tea Research Association (TRA), Darjeeling Advisory Centre, said.

“Darjeeling has not been receiving adequate rain that can support the first flush. Dry season coupled with scanty rainfall has been taking a toll on the crop the last 4-5 years,” Laskar said. Urbanisation and labour shortage add to the problem.

Data from TRA shows that the crop in April 2025 was 25 per cent lower than April 2024 and 32 per cent lower than April 2023.

Cumulatively, till April, production was 7 per cent less compared to 2024 and 15 per cent vis-a-vis 2023. 2024 was marked by lower production on account of weather.

“If monsoon arrives in the first week of June, the period of second flush may be shortened, which means availability of top quality tea will be less,” said Ashok Lohia, chairman of Chamong Group — the largest producer of Darjeeling tea with 13 estates producing 1.1 million kg.

Fading charm?

Darjeeling breaks economic logic — the falling supply of the golden elixir has failed to ignite strong demand.

“The irony is that production is now less than 6 million kg, but even that is struggling to fetch good prices,” Lohia pointed out.

Large buyers in the international market think they are overpaying, he said.

A white paper by the Indian Tea Association (ITA) on Darjeeling earlier this year showed that the share of exports vis-a-vis production was 51.67 per cent in 2021 and 41.09 per cent in 2023.

Demand in the export market has come down due to a hangover from the 2017 strike, influx of Nepal teas, weak currencies in major importing countries, according to Anshuman Kanoria, chairman Indian Tea Exporters Association (ITEA).

“In the domestic market, the retail sector is so huge that there is no supply chain trade integrity in the domestic market. The supply chain integrity of GI of Darjeeling is only at the first stage – at the time of production, sale and in export,” Kanoria added.

The financial squeeze

Relatively speaking, the Darjeeling estates are small. The average size of a garden in Darjeeling is 150 hectares, compared to 450-500 hectares in Dooars and Terai, the white paper mentioned.

The average yield in Darjeeling is 350 kg per hectare compared to 1800 kg per hectare in Dooars and Terai. In 1990, though, the yield per hectare in Darjeeling was 723 kg.

Given that the fixed costs are the same, the break-even point is much higher.

A large part of the industry has been reeling under losses, pointed out ITA’s Raha.

“Darjeeling tea needs a bailout which will enable it to replenish its assets and put in better climate mitigation infrastructure. This is what the last Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce had recommended.”

Production hit 5.6 million kg last year. “If it dips lower, some gardens will close down,” a major producer pointed out.

A Parliamentary Committee visit to Darjeeling is on the cards this month. Will that lead to a lifeline for Darjeeling tea?

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff