India’s equity markets may have expanded rapidly, but initial public offerings (IPOs) are increasingly becoming exit vehicles for early investors rather than as engines for raising long-term capital, a shift that undermines the spirit of public markets, Chief Economic Advisor V Anantha Nageswaran warned on Monday at a CII event.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff

Of the nearly Rs 94,000 crore raised by the top 15 IPOs of 2025, three-fourths (almost Rs 68,700 crore) came through secondary share sales.

Five of these 15 IPOs were entirely comprised of sales by promoters or private equity investors, while the remaining 10 offered a mix of primary and secondary components.

Nageswaran also cautioned against celebrating “wrong milestones” such as rising market capitalisation ratios or surging derivatives volumes, arguing that they do not reflect genuine financial sophistication and may instead risk diverting domestic savings away from productive investment.

“While we have succeeded in developing a sophisticated and robust capital market, imbibing some of the best practices from the developed world, although they may have abandoned them.

“But this may also have contributed in part to more of short-run earnings management optics because they are linked to executive compensation and market capitalisation increase, which also boost the value of stock and options, etc,” said Nageswaran.

All of this, he added, has played a role in inhibiting long-term financing and channelling ample cash reserves into financial instruments rather than real-world investment.

“So, there is a need for ambition, risk-taking and long-term investing, otherwise India will find itself falling short with respect to strategic resilience, let alone building strategic Indispensability in the world where we want to be one of the largest players in the coming years,” he said.

Tuhin Kanta Pandey, chairman of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi), called for a more accommodative view on IPO structures.

“The mix between primary and secondary components varies from one IPO to another. Many companies have already raised primary capital at an earlier stage, which is why existing investors often choose to exit during the IPO.

There are also instances where companies raise fresh capital to fund greenfield projects.

In my view, the capital market should accommodate all such objectives,” said the Sebi chief during the event.

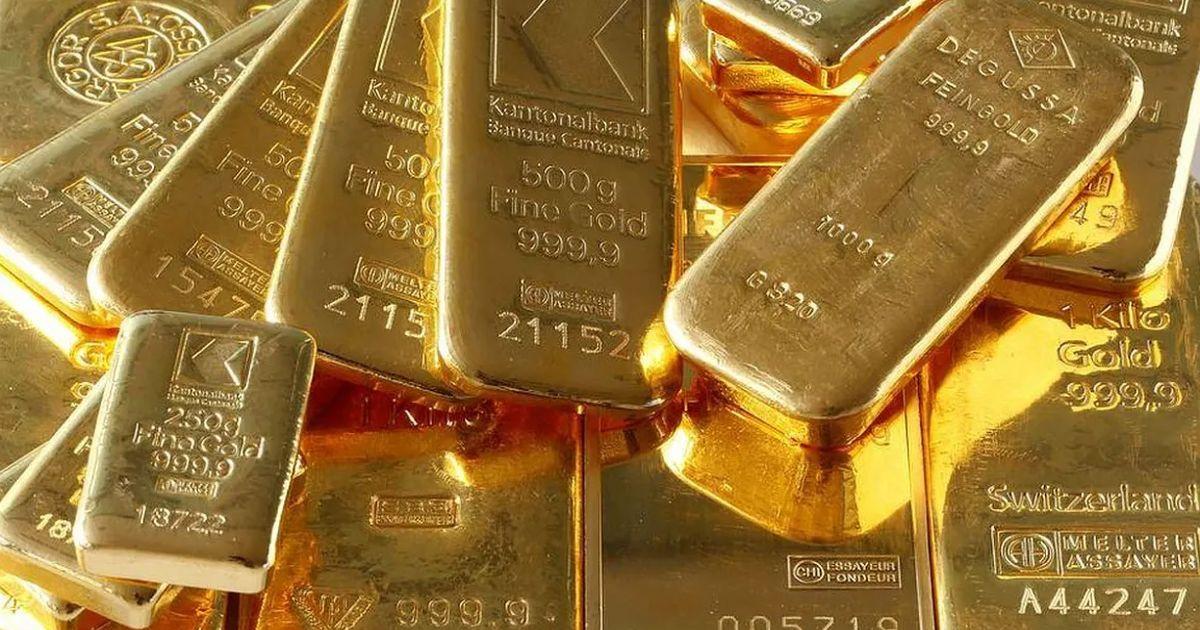

The chief economic adviser also emphasised that if capital continues to gravitate along geopolitical fault lines, external financing alone will be insufficient to meet the scale of India’s development ambitions.

“If India is to fulfil its aspirations, the primary drivers of financing must increasingly come from within.

“External capital can and should supplement our efforts, but the strategic burden must rest on domestic institutions. Uncertainty can only be blunted by institutional strength at home, and our financial sector must evolve into our most reliable source of stability,” said Nageswaran.

He further warned that a potential bust in the AI boom, flagged by the International Monetary Fund in its global economic outlook, could mirror the severity of the dot-com crash, with any unwinding likely to slow economic recovery and deepen the consequences of capital misallocation.

“This should caution us against complacency. India cannot allow its financial sector to drift away from the real economy, nor can we afford vulnerabilities created elsewhere to spill over into our markets.

“Stability, resilience and alignment with national priorities must anchor our financial system,” he said.

Sustaining India’s growth trajectory on its path to becoming a developed economy, he argued, will require strengthening domestic drivers across four high-priority areas: Industrial upgrade moving from assembly to higher value-added production; harnessing the demographic dividend; achieving near-energy self-sufficiency; and deepening innovation capacity.

Nageswaran also stressed that business-as-usual financing models will not suffice in an era defined by uncertainty and technological disruption.

“Past credit cycles have left scars, leading to a preference for short-term lending, collateral-heavy underwriting and a tilt towards incumbents over innovators.

“If India is to build productive capacity for the next decade and beyond, our financial institutions must provide patient, lockdown capital that supports enterprises across their full growth trajectory, not just their immediate credit needs,” he said, asking banks and financial institutions to become bolder, technologically sharper and more willing to take calculated risks.

He underscored that India cannot rely predominantly on bank credit for long-horizon financing.

“A deep and reliable bond market is a strategic necessity, particularly for financing long-term national objectives. Insurance and pension funds, whose horizons naturally align with long-term investments, must play a larger role,” he said.

The edifice of such a bond market, he added, would depend on trust and transparency, commitments that corporate leadership must uphold on a durable, demonstrable basis.

With inputs from Samie Modak