Several executives argue that UPI has the potential to grow tenfold, but warn that the absence of a monetisation model risks stagnating the real-time payments system, which has been recording all-time-high transaction volumes every year.

Illustrations: Dominic Xavier/Rediff

India’s most successful digital payments story — the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) — is free for consumers but far from costless.

As Reserve Bank of India Governor Sanjay Malhotra recently reminded, someone is footing the bill, and for now, it is the government.

That raises a pressing question: How long can subsidies sustain UPI’s explosive growth? The government wants transaction volumes to expand tenfold, but industry participants, including fintechs and banks, say the UPI ecosystem may be nearing a tipping point where technology and operational costs are difficult to absorb.

Several executives argue that UPI still has the potential to grow tenfold, but warn that the absence of a monetisation model risks stagnating the real-time payments system, which has been recording all-time-high transaction volumes every year.

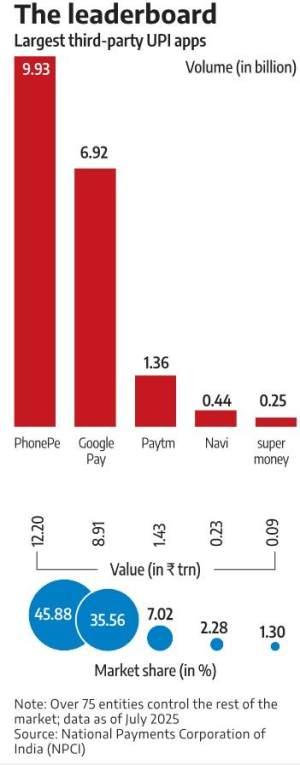

In July, UPI processed a new high of 19.46 billion transactions worth ₹25.08 trillion.

Of these, nearly two-thirds (63.63 per cent) were peer-to-merchant (P2M) payments; the remaining were peer-to-peer (P2P) transfers.

In July, P2M transactions stood at 12.38 billion in volume and ₹7.34 trillion in value.

The industry cautions that without monetisation, sustaining this pace might prove difficult.

As a solution, the stakeholders have been pressing for the introduction of a merchant discount rate (MDR) on UPI P2M transactions.

The proposal is simple: Spread the cost across the ecosystem, with each stakeholder earning a share for supporting the infrastructure.

Earlier this year, the Payments Council of India (PCI), which represents digital payment players, wrote to Prime Minister Narendra Modi seeking a 0.30 per cent MDR on transactions at large merchants.

Who pays how much for what

Consumers pay nothing for using debit or credit cards, or UPI. But merchants pay a percentage of the debit or credit card transaction amount — an MDR — to a payment processing company. They, however, pay nothing for UPI transactions.

For debit cards, an MDR of up to 0.90 per cent of the transaction value is applicable across all card networks.

There is, however, no cap on MDR for credit cards. Typically, credit cards (non-RuPay) attract an MDR of 200-300 bps.

Usually, the issuing bank takes 60 per cent of the MDR, and the balance is shared between the network provider (Visa, Mastercard, etc) and the acquirer.

According to the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), the umbrella organisation that facilitates services like UPI payment, Bharat BillPay, RuPay, FASTag etc, an MDR of up to 0.30 per cent is applicable for UPI P2M transactions.

However, to promote digital transactions, the MDR was brought down to zero in January 2020 for RuPay debit card and BHIM-UPI transactions through amendments to Section 10A of the Payments and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 and Section 269SU of the Income-tax Act, 1961.

To help the payment ecosystem’s participants deliver the services effectively, the government has implemented the ‘Incentive Scheme for Promotion of RuPay Debit Cards and Low-Value BHIM-UPI Transactions (P2M)’.

Under this scheme, the government pays the incentive to the acquiring bank (merchant’s bank), which then shares it with other stakeholders: The issuer bank (customer’s bank), the payment service provider bank (that facilitates UPI onboarding/API integration), and third-party app providers.

Solution at hand?

However, that support is shrinking. The 2025-2026 financial year (FY26) subsidy for UPI P2M and RuPay debit card transactions has been slashed to ₹437 crore — down 78 per cent from the final outlay of ₹2,000 crore in FY25, and much lower than the ₹3,631 crore approved in FY24.

This marks the second consecutive year when incentives for promoting digital payments were reduced.

The final allocations for the incentive scheme, launched in April 2022 with an initial outlay of ₹2,600 crore, is often higher than the budgeted amount.

For instance, in FY25, the initial allocation was ₹1,441 crore, which was later revised upward to ₹2,000 crore.

The payment industry’s estimates peg the annual requirement closer to ₹10,000 crore to maintain and expand UPI services.

With no MDR on UPI P2M transactions, several private sector banks — including ICICI Bank, Axis Bank, and Yes Bank — have started charging payment aggregators a fee for handling UPI transactions on merchants’ platforms.

The move aims to offset the rising costs from the surge in such transactions, and to build capacity for handling growing volumes.

Experts say more banks are likely to follow suit, given the exponential rise in UPI transactions, particularly in the P2M segment.

This trend, they add, further strengthens the case for introducing MDR on UPI P2M transactions, enabling ecosystem players to share the fee and cover their costs more effectively.

“Banks have been charging [a fee] for a long time; this is not new. Some charge directly as a transaction percentage,” says a top executive at a payment aggregator, requesting anonymity.

“Then, there are those who charge a fee to bring a merchant on board, or there are some charges if the merchant has not been active for a long time.”

Another executive, who also does not wish to be named, says that for him, at least one out of two transactions are on UPI.

“When a bank fee is notified, I cannot absorb the cost entirely, and will eventually pass it on to the merchant,” this executive says.

Industry players add that while other monetisation-friendly avenues are emerging for UPI, those require to be developed further to offset the impact of free transactions.

One such avenue is RuPay credit on UPI guardrails.

‘Credit card usage on UPI has grown significantly,’ says an executive quoted above.

“It’s a natural monetisation opportunity within UPI, which often gets overlooked, but has been steadily increasing. A certain percentage of UPI transactions are done on credit, and we stand to earn revenue from those.”

Currently, 400 to 450 million people use UPI every month. Dilip Asbe, managing director and chief executive officer of NPCI, believes it has the potential to grow to over one billion.

To sustain such rapid growth, industry participants insist MDR is essential since it would help fund acceptance and servicing, and infrastructure acquisition.

However, every time there is a suggestion that the central government might consider a fee for the UPI P2M framework, the finance ministry swiftly and strongly rules out any such plan, reiterating that UPI is a ‘public good’ critical to India’s productivity.

For now, the costs are spread thin, even as UPI continues its meteoric rise.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff