The story of the Bombay Stock Exchange and the people who shaped its growth: From wars and bomb blasts to speculators, reformers and wealth creators.

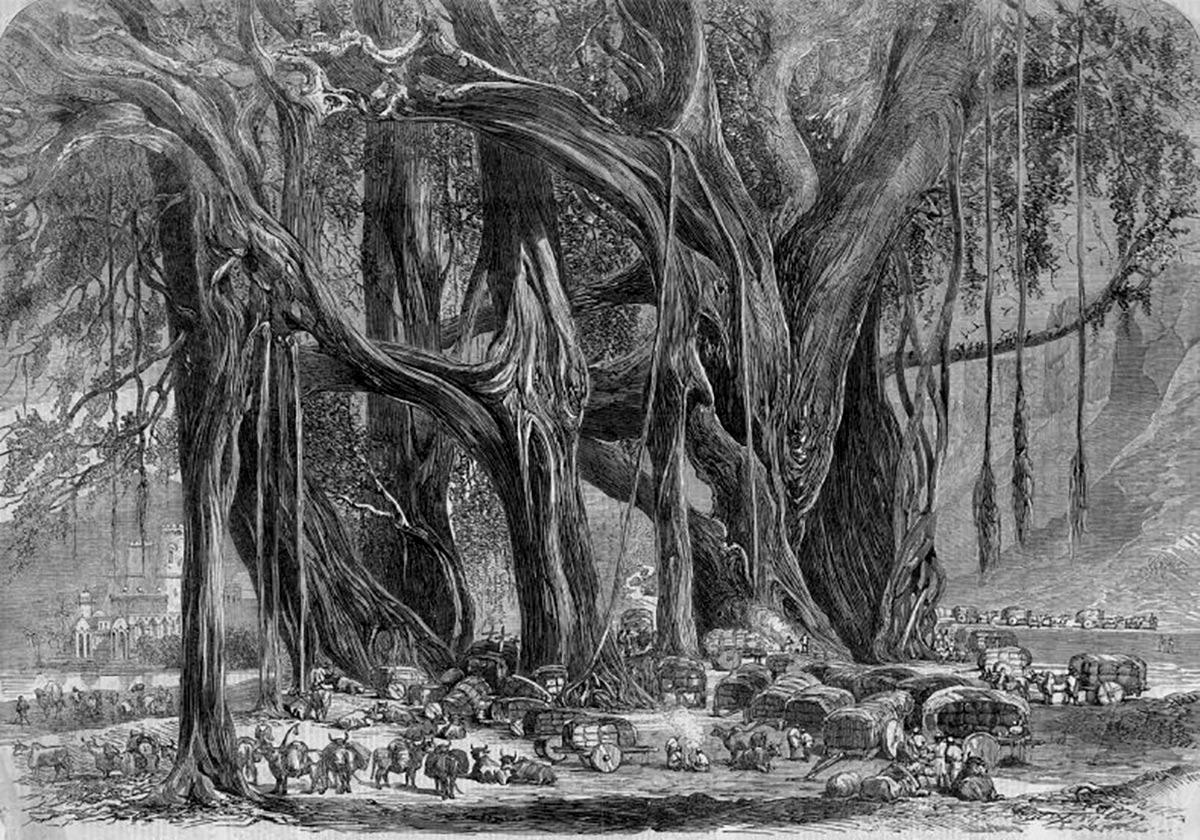

IMAGE: The informal beginnings of what would become the Bombay Stock Exchange can be traced back to the 1850s. A group of around 20-22 stockbrokers began meeting and trading under a banyan tree. Photograph: Kind courtesy Wikimedia Commons

In some ways, the history of the BSE can be traced back to the speculative mania that gripped Mumbai (then Bombay) more than a decade before the exchange’s founding.

Among the key figures of that great bubble was Premchand Roychand, described as a ‘devout Jain, of fair complexion, lithe of limb and sweet of temper, of engaging manners and free from the pride of riches — who had seen no more than thirty-four summers but who carried a most clever financial head on his shoulders.’

Roychand was involved with financial institutions like the Bank of Bombay and the Asiatic Bank.

He had started out as a share broker at the age of 16 and by the 1860s was foremost among brokers who traded in shares at various locations in Mumbai, absent an exchange. This was a fortuitous time to be in the business.

The East India Company’s control over the country ended with the mutiny of 1857.

The British crown was in direct control and there was free flow of capital into India without the barriers placed by the Company Raj.

Tea and coffee plantations abounded, as did jute mills and coal mines. Then the American Civil War choked cotton supplies to Britain, which bought up cotton from India to fill the breach.

The resulting flow of wealth into the country saw a surge in speculative activity in shares of newly formed enterprises and even derivative trading through a kind of forward contract called a time bargain.

IMAGE: The Bombay Stock Exchange. Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/Reuters

Roychand helped funnel banking funds into the booming stock market, often with little room for prudence or caution.

Sorabjee Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy recalled in testimony of a visit by Roychand on a monsoon day in July 1864, asking if he had managed to purchase any shares of the Bombay Reclamation company, one of the darlings of the boom. Jeejeebhoy, in his Malabar Hill bungalow, said that he hadn’t.

Roychand told him that he would manage to get him some shares and asked how many he wanted.

Jeejeebhoy replied that he didn’t have too much money at hand to invest and that he would perhaps buy no more than a few. Roychand would have none of it.

‘Take my word, Sorabjee, and do not trouble yourself about money. I will get you as much as you require. But do not go in for less than one hundred shares,’ Roychand said.

The surprised Jeejeebhoy was told that Roychand would arrange a loan of ₹10 lakh for him from the Asiatic and the Bombay Bank.

He subsequently sent him two letters, one addressed to an Asiatic Bank official (a Mr Morrison) and a similar one to a senior person (Mr Blair) at the Bank of Bombay.

The note simply said, ‘My dear Mr. Blair, could you accommodate Sorabjee with five lakhs?’ The note to Morrison was similar. Both readily agreed.

IMAGE: The crash of 1865. Photograph: Kind Courtesy, Illustrated London News/Wikimedia Commons

Jeejeebhoy found, however, that even ₹10 lakh was insufficient for 100 shares amid the boom, and placed an order for 43.

He received the shares in a few days and found that the sellers included Roychand, his father, his brother-in-law and other directors of the Bombay Reclamation Company. The insiders seemed to be selling. But they may not have got out soon enough.

The mania ended suddenly in 1865 with the cessation of the American Civil war.

Roychand lost his fortune as did the richest merchant princes of Bombay, such as Behramji Hormusji Cama and Kharshedji Furdunji Parekh.

But the boom laid the foundation for stock brokers to become a force in India. There were perhaps half-a-dozen share brokers between 1840 and 1850 recognised by banks and merchants.

They would meet at Cotton Green. By 1860 there were 60 brokers who met now between the old fort walls in town and the old Mercantile Bank.

Their numbers rose to 200 to 250 during the mania and their business was conducted unhindered on streets, shops and banks, often obstructing other activities. Their popularity and numbers waned after the bust of 1865.

IMAGE: Premchand Roychand. Photograph: Kind courtesy Wikimedia Commons

In 1875, a little more than two dozen brokers formed an association by contributing ₹1 each.

The Native Share and Stock Brokers Association of Bombay whose members had once traded under a banyan tree, decided to hire a trading hall. But found itself short of funds to pay the ₹100 in monthly rent.

Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, a wealthy merchant and textile mill founder, gifted 25 shares of his company Victoria Manufacturing to the association, partly to also pay for some brokerage he owed to some of the members.

The shares were sold at ₹690 to raise ₹17,250. The association returned Petit’s advance with the money and used the remaining capital to commence operations.

The Association was formally constituted on December 3, 1887 and grew to 361 members by 1909. Seth Chunilal Motichand was its first president.

Trading in the initial days was said to be limited to a few textile shares and some government securities.

It was World War I which acted as a catalyst for growth in the early 1900s, much like the earlier conflict on foreign soil: the American Civil War in the 1860s.

The import of goods from England became difficult. Indian companies made money hand over fist as they supplied the war effort. The surge of capital was invested in new companies.

The share market was once again booming and the brokerage business boomed with it. The value of a Bombay Stock Exchange membership card rose from ₹2,900 in 1914 to ₹48,000 in 1921.

IMAGE: Dinshaw Maneckji Petit, industrialist and philanthropist who founded the first textile mills in India. Photograph: Kind Courtesy, Wikimedia Commons

Rising stock market activity saw more ‘corners’. Those who believed a stock would fall in price would short-sell it.

For example, an entity with a negative view on a company (a bear) would sell shares of a textile mill at ₹100, even if they didn’t own it. Assume the share price fell to ₹80.

They would buy shares at the lower price to close out their position, and pocket the difference of ₹20 per share.

Sometimes they wouldn’t be able to buy back as many shares as they had sold. This resulted in them being backed into a corner.

Those who held the shares could demand any price they wanted for the bears to avoid a default, resulting in wild swings; and also the chance for manipulation.

Many with a positive view on the stock (called bulls) could also buy up shares from the market to trap the bears.

The trapped bears would often be forced to sell their other holdings at steep discounts, often leading to panic and crisis.

Such corners were rare before 1918.

This became more common later with corners declared in Fazulbhoy Mill in February 1921 and Currimbhoy Mill in July 1921 and Finlay Mill in January 1922.

Corners were also attempted in Nagpur, Swadeshi, Currim and David Mills in 1922.

‘Prices were likewise in that year fixed in the shares of Shri Shapurji Broacha Mill. Prices in the shares of the Kohinoor Mill have been fixed twice in 1923 and even while this Committee was in session a corner was declared and prices were fixed in the shares of the New Great Eastern Spinning and Weaving Company… The bare enumeration of these corners conveys but a faint idea of the dislocation and disturbance of the market thereby occasioned,’ according to the 1924 report of the Bombay Stock Exchange Enquiry Committee.

The committee headed by former London Stock Exchange chairman Sir Wilfrid Atlay found laxity in the working of the Association.

Regulations were difficult to ascertain. Some rules were not printed or published and there was no way for the public, or even the brokers, to ascertain exactly which rules were in force.

Speculation built up again even as the government was contemplating action. There was a crash and panic in 1925. The government subsequently passed the Securities Contract Control Act of 1925.

It was around this time that K R P Shroff became the exchange’s president, among the longest-serving of the many expert crisis-handlers who became heads of the BSE.

He served the exchange from 1923 to 1966, a tumultuous time which saw the struggle for Independence, a world war, freedom, and multiple wars with neighbours.

A school teacher in his early days, he joined his father in his business as a broker in 1902.

IMAGE: 1924 Bombay Stock Exchange: Sir Wilfrid Atlay. Photograph: Kind courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Despite the 1925 legislation there were crises in 1928, 1930, 1933, 1935 and 1936; even as India reeled from the effects of the Great Depression.

Then came the second world war. Share prices rose at first. The sudden fall of France in 1940 shocked the markets in India.

The Calcutta Stock Exchange was shut for six weeks. Forward trading was stopped on the Bombay Stock Exchange and minimum prices were fixed for all shares!

The market soldiered on. The government instituted the Defence of India Rule 94C on September 24, 1943 which restricted forward and derivative positions to curb speculation.

The result was that speculation moved off the organised exchanges and onto what became known as the ‘grey market’ in Bombay and Ahmedabad; and ‘Katni’ market in Calcutta. These markets soon became bigger than the exchanges themselves. Eventually sanity returned.

Shroff collaborated with government committees while defending the position of brokers.

He was said to be involved in key early legislation such as the Bombay Forward Contracts Control Act, 1947, and the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Rules promulgated by the government in 1957.

He initiated the publication of analysis reports of companies and laid the foundation for modernisation.

IMAGE: The Bombay Stock Exchange: Inset: Dinshaw Maneckji Petit. Photograph: Reuters

Phiroze Jeejeebhoy was the chairperson of the exchange from 1966 to 1980. One of his most enduring legacies is the towering structure which still houses the BSE.

Construction began in 1973 even as government policies had begun to take a sharp anti-market turn. Moraji Desai banned forward trading. Indira Gandhi shifted further to the Left with nationalisation.

Jeejeebhoy reportedly called Nimesh Kampani to explain his difficulties with the building of a new tower during such difficult times, according to Sameer Kochhar’s 2015 work BSE: Journey of an Aspiring Nation.

‘I am telling you privately that the Exchange needs money because the building work has to be completed and if we get stuck in-between, then we are in trouble.’

Kampani helped organise short-term funding for the exchange to complete the building.

The idea was perhaps to rent out space within the tower to ensure cash flows. It was eventually completed in seven years. It was named after Jeejeebhoy after he passed away in 1980.

The tower became iconic, and later a target.

IMAGE: Controversial stockbroker Harshad Mehta arrives at the Bombay high court, November 9, 2001. Photograph: Arko Datta/Reuters

M R Mayya, chief executive officer of the BSE in 1993, was making his way down to the parking lot of the building when the exchange was targeted in serial bomb blasts.

The explosion had ripped through the building by the time he reached downstairs. Vehicles were trapped, phone lines stopped working.

‘I escaped death by a hair’s breadth… I then went to the police commissioner’s office, virtually on foot,’ Mayya told Business Standard in 2013.

Those who were outside the exchange, grabbing a quick snack from the large number of food vendors on the streets, had shattered glass rain down from them from above.

The blast at the exchange and elsewhere including the iconic Air India building and Plaza cinema killed 257 people.

This likely marked the worst in a decade of terrible turns for the exchange. The Harshad Mehta scam pushed for the creation of its now larger rival the National Stock Exchange.

Physical trading gave way to electronic screens and the tight grasp of Bombay’s brokers over the nation’s equity markets loosened.

But the exchange reinvented itself. It now boasts advanced co-location facilities on par with global peers which allow for hundreds of thousands of trades in a fraction of a second — a far cry from the hand signals that dominated manual trading as recently as the 1990s.

In recent years it has gained substantial portions of the market share it had lost to the NSE. It has managed to list ahead of its larger rival managing the feat in 2017. It is currently valued at over ₹1 trillion.

Not bad for an exchange which began with contributions of ₹1.

Building BSE

- July 9, 1875: Native Share and Stock Brokers’ Association formed

- January 1899: Acquires new building on Dalal Street

- July 28, 1914: World War I begins, Indian stock market booms

- April 1920: Exchange acquires adjoining building as its business expands

- August 31, 1957: Gets permanent recognition under Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act

- January 2, 1986: BSE Sensex, country’s first equity index is launched

- March 14, 1995: Launches on-line trading (BOLT) system

- June 9, 2000: Brings in equity derivatives

- April 1, 2003: Introduces T+2 settlement

- August 19, 2005: Becomes a corporate entity

- February 7, 2006: Sensex closes above 10,000

- January 4, 2010: Market time changes to 9 am to 3:30 pm

- March 13, 2012: Launches SME exchange platform

- February 3, 2017: Becomes a listed entity

- May 14, 2025: Crosses ₹1 trillion valuation

Key references

The Failure of The Bank of Bombay, 1840-1868 (Carol Grace Lovell, 1971)

A Financial Chapter In the History of Bombay City (D E Wacha, 1910)

Report on Bombay Stock Exchange Enquiry Committee – 1924 (Sir Wilfrid Atlay)

Report of the Stock Exchange Enquiry Committee (Walter B Morison, 1937)

Report on the Regulation of the Stock Exchanges in India (P J Thomas, 1948)

BSE: Journey of An Aspiring Nation (Sameer Kochhar, 2015)

Photographs curated by Manisha Kotian/Rediff

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff